Thoughts on Devon Island

Sunday August 22, 2014 (73o 52’N 90o 18’W): Port Leopold

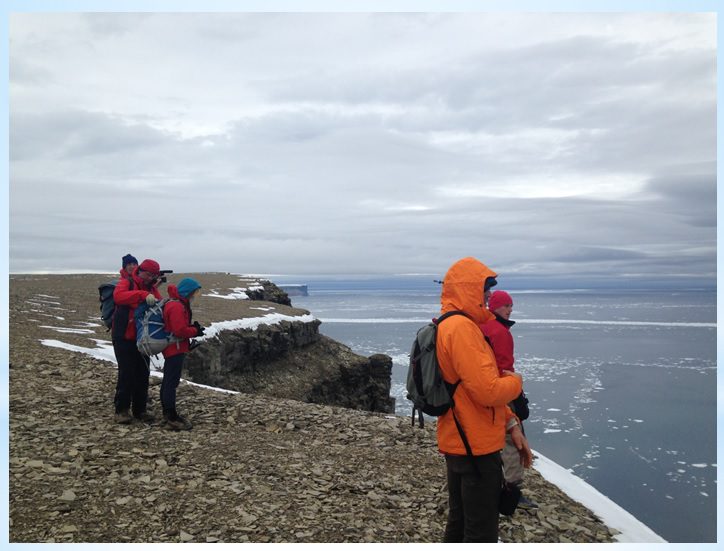

Since Friday, we have remained anchored in Port Leopold along with the yachts Catryn, Drina, and Gyoa. Together with their crews, we’ve been going on long walks on the neighboring bluff and having daily meetings to share information and opinions as to whether or not the ice will open in time to allow a passage. For us, the 28th of August remains the deadline to decide whether to attempt to go forward through the Passage, or head back east and down the coast of Baffin Island then on to Maine. Either way, will mark a retreat from the high arctic.

Back in mid-August, while looking out over Erebus and Terror Bay, I consciously told myself that this was most likely the farthest north I would ever travel. Pulling out my cell phone, I took panoramic shots of the land and sea surrounding the boat, aware that it would only record literal images unable to capture the profound loneliness of the high Arctic.

Erebus and Terror bay is on Devon Island, reported to be the largest, uninhabited island in the world. More correctly, it is uninhabited by humans, while home to the wide variety of sea life that startled us one evening with their feeding frenzy. And home to the birds flying above the frenzy, and the polar bears and other land animals evident mostly through their paw prints and dropping. We are the intruders. Walking in the desert valley between the bluffs seemed endless.

The terrain is starkly uniform on the grand scale, but surprising varied and structured up close. Endless shattered plates of slate are punctuated by the odd rock or fossil that looks as if it has no natural reason to be there. And the water run-off and frost heaves create patterns that look as if they must be the design of intelligent beings, like the canals on Mars.

Occasionally, an isolated mossy patch of green would merit investigation and reveal the decomposing remains of an animal providing nourishment for the plants. But mostly, Devon Island appeared devoid of life.

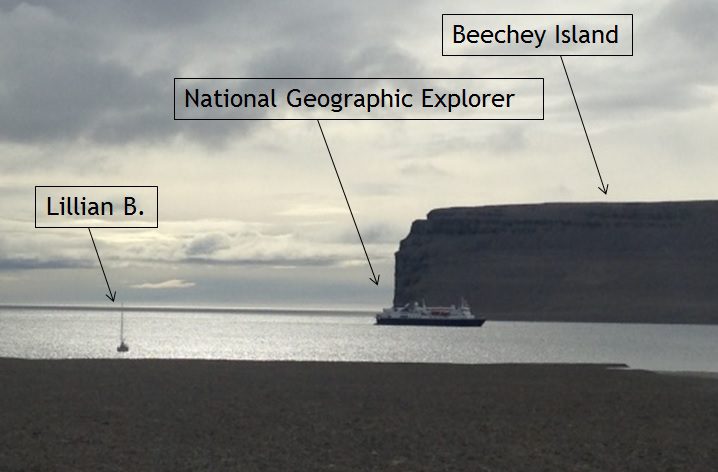

And Beechey Island, with its collection of human graves, is itself a monument to the desperate loneliness of Devon Island. Franklin’s crew intruded and wintered at Beechey while trying to find the Northwest Passage, leaving behind the bodies of those who did not survive. Those who did survive that winter would continue on to a similar fate. Even in Summer, contemplating the depth of their hardship generates disbelieve and fascination. More than the appeal of history, I suspect it is that fascination that motivated the National Geographic Explorer Cruise ship we saw in the harbor to travel as far North as Erebus and Terror and ferry boatloads of passengers over to visit the graves.

We motored to Beechey and visited as well. The graves on the east side are aligned in a row, but with the last one slightly out of place, as if the desire of the living for creating order, out of respect for the dead, was overcome by fatigue or depression. Or perhaps they tried to place the last one in line, but were unable to dig through the rocks, doing the best they could in harsh conditions. Either way, looking at the graves, the desperation of the men who dug them seeps through time, like the oil droplets that still drift up from the entombed Arizona in Pearl Harbor. Devon Island was a desolate place of stark beauty.