South Pacific: What Would Dave Do (WWDD)

The first time I met Dave Dickerson was on the eve of the winter solstice, 2000, on a blustery night in Gloucester Harbor, Massachusetts. He and his daughter Heidi were in the process of delivering the Lillian B., then Carpe Diem, from Westbrook Connecticut to Rockport, Maine. They were hurrying northward under the threat of December frontal weather, in a rush to get the boat to Johanson Boatworks before winter set in. By next summer, Lillian was to be ready for the charter season. As the new owner, I had asked Dave if I could ride along on part of the delivery, resulting in our rendezvous in Gloucester. Once on board, he provided me with a safety briefing, boots, and a bright orange “Mustang” to guard against the cold.

As darkness fell and the winds rose to over 30 knots, we “stuck our nose out” (as Dave would say) into the darkness as a light snow pelted the deck. For the rest of the night, I sat huddled in a corner of the cockpit as Dave and his daughter steered the boat before the wind. At regular intervals, frigid water would douse us from over the stern, as if thrown from a bucket off stage. The boat rose and fell with the following waves, which were illuminated by the glaring white stern light. Around 2:00 in the morning, the rolling motion combined with the cold led to the loss of the large bowl of beef stew that Heidi had offered, and I’d consumed, hours before. After that relief, the queasiness vanished, but the chill remained. At regular intervals I would manually pump the bilge, mainly in an attempt to generate body heat. Ice formed on the railings and stainless steel rigging. High above, the constellation of Orion marked the hours as he arched across a clearing frigid sky. I fought sleep, not wanting to miss the sunrise. I was rewarded for my stubbornness by the pale warmth of dawn off Monhegan Island. By mid morning the winds had abated and I took the helm for the first time. Shortly after mid-day we glided into a deserted, cold, gray Rockport harbor, much to the astonishment of a handful of spectators.

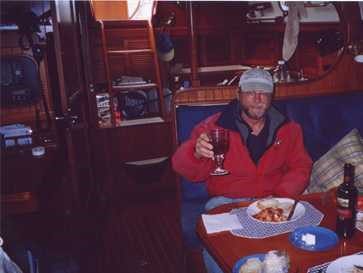

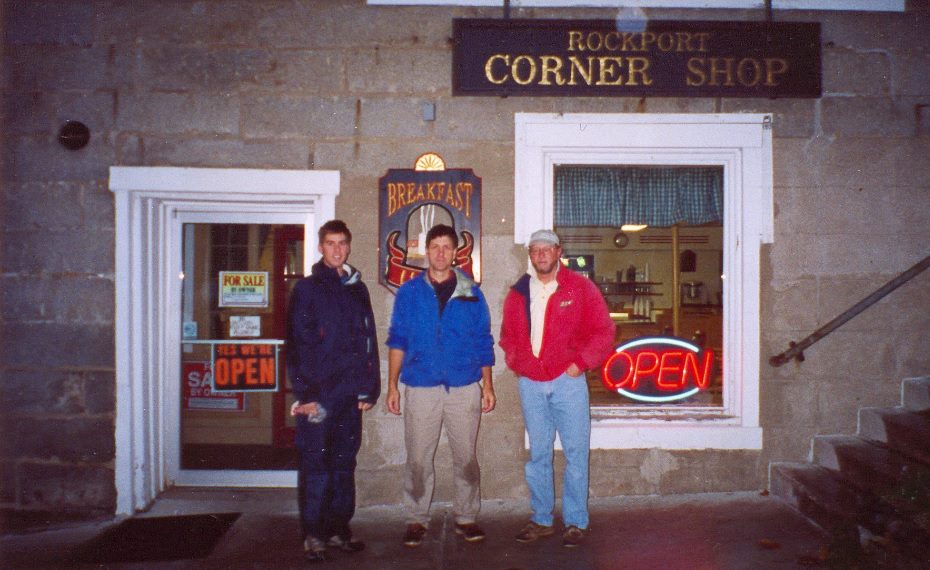

Four years later, Dave and I met again on board the Lillian B. on a gray day in Rockport Maine. This time it was an early November morning after a hardy breakfast of blueberry pancakes, eggs and bacon at the Rockport Corner Shop. I had asked Dave to help me and my nephew Peter gain some fundamental knowledge and proficiency in bluewater sailing in preparation for our extended trip to the South Pacific. The first leg was to be from Maine to Florida, where Lillian would be docked over the winter in preparation for a February departure. Stocky, bearded, with a trace of red in his hair, Dave has a vitality and robustness that match well with his image as a man of the sea. Quick to smile, he can also exhibit a sharpness when someone doesn’t adhere to the rules. “First come, first serve” he would radio to a powerboat trying to usurp our place at one of the locks on the intercoastal waterway, “ take a number.” Schooled at the SUNY Maritime Academy, he has spent his life on or near the sea. Everywhere we went there was a story. In New London, he had worked for Electric Boat and conducted sea trials of nuclear subs. In New York harbor, he had worked on tugs, and confidently guided Lillian through the evening ferry traffic. On the Intercoastal Waterway (ICW), he knew the names of most of the places and many of the people along the route. Recreation for Dave is world class ocean racing. His wife and all four of his daughters are avid sailors, and at least two have competed on an international level.

At sea, Dave would continually be checking weather, our position and the surrounding traffic. Safety equipment was checked and used. During the first part of the trip, he often slept on deck to be close at hand in case he was needed. Approaching land, the maps and guides were double-checked. When available, radio contact was made to obtain or verify the local conditions. Before entering a harbor or approaching a dock, the tide, winds and currents were known. At the dock, the engine and other systems were inspected and maintained.

For Peter and me, Dave’s professionalism serves as an example, that if we follow it, we’ll do all right. On the last day of the trip we presented Dave with an old T-shirt upon which we had written “WWDD.” (What Would Dave Do). I don’t think Dave quite understood the reference, but Peter and I appreciate the meaning.

– January 2004